The Breakfast Club: Enduring lessons for stronger school-based relationships

It was September 2020. Roughly 6 months had passed since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. By the end of August, our Superintendent had announced that our school district would remain on remote instruction through mid October 2020, and potentially for the entire 2020–2021 school year. As a passionate school-based occupational therapist, with 14 years of hard-earned experience under my belt in a challenging inner-city setting, I had seen my fair share of challenges and unpredictable scenarios. Still, with this announcement I felt an unfamiliar sense of uncertainty, even inadequacy. I asked myself how I could find the strength to approach a new school year unlike any other. I, your typical push-ahead, go-getter, type-A school-based OT practitioner was very experienced in writing therapy schedules, negotiating time slots, conducting early therapy screenings, and covering overflow summer evaluations.

I was not, however, prepared for the 2020–2021 school year. I was unprepared for the full-blown loneliness, the lack of daily structured schedules, and the unknown of negotiating time slots with teachers and students who had yet to firm-up a schedule—in an environment that seemed to change hourly. My schedule, teachers, students, colleagues, and school were all moving targets. I was essentially alone in my kitchen, attempting to be a school-based occupational therapist without a school, classroom, student, or teacher in sight.

I felt helpless, alone, and untethered for the first time in my career. At the same time, I knew, with certainty in my bones, that I was not alone in my loneliness, in the helplessness, or in the feeling of being untethered. We were all together in these emotions. I also knew that we had to attack this loneliness together to be successful with our students. Soler-Gonzalez and colleagues (2017) describe how friendships and connections are not only necessary for health care workers on a personal level; they are necessary for occupational function. A health care worker needs human connection in order to nurture and give to others—within their occupation. Loneliness, or lack of connection, is therefore naturally detrimental to a therapist’s capacity as a giver. As a team, we needed each other more than ever, both professionally and personally.

The group of therapists at my school, consisting of the physical therapist, speech therapist, and myself, were wholly supportive of each other. Yet, as Giess & Serianni (2018) state, like most school-based interprofessional teams, we praised the potentiality of collaborating, while struggling to find time to actually collaborate. We had been a team for more than 5 years in the same school, but we had not successfully planned or implemented a long-term collaborative initiative schoolwide.

A Novel Solution: Transforming Constraints Into Collaboration

With all the uncertainty, it became necessary for our therapy team to plan and work together in a way that had never been so vital before. In early September 2020, we gathered online to plan the year. We discussed therapy methodologies, scheduling strategies, evaluation, and screening techniques. That is when the revelation hit: the constraint of no school building, schedule, or location was actually a strength. We were no longer limited by a physical location or our own pre-determined schedules. Xyrichis and Williams (2020) make a similar point, stating the need to embrace online methodologies during the pandemic, which intrinsically allows for more flexibility and agility. As a therapy team, we could now finally merge our schedules to plan what we had always said we would: a full interprofessional collaborative initiative at our school. While comparing scheduling notes, we discovered that all the teachers at our school had class starting no sooner than 8:30 am, yet the school day technically started at 7:50 am. We had a free window, an opening, a chance. We took this window and made it our own.

We called this window The Breakfast Club, and planned a therapy initiative together for this time slot each day. We made our own website and curriculum, and we pulled from our students’ goals to create activities. We made it voluntary and invited every classroom from our elementary school to participate. In early September, we averaged five students per day. By December 2020 and January 2021, The Breakfast Club included school-wide participants from a range of classrooms in preschool through fifth grade levels, in both special and general education settings. School administrators occasionally attended, and so did the district evaluators and case managers. They knew where to find the school therapy team, as well as many classroom teachers and students each day from 8:10 am to 8:35 am.

What we didn’t expect was that this way of adapting to COVID-19 would teach us, as a therapy team, so much about the potential impact of school-wide interprofessional collaboration. We would later learn that intentionally designing this program for the whole school improved personal self-efficacy of participating teachers and therapists, while additionally impacting engagement and culture at the school-wide level.

Daily Breakfast Club Approach

Each day at 8:10 am, participating therapists and teachers logged into the Online Learning Classroom. A waiting room was set up to protect students and staff. A typical structured schedule for our group is described below:

- Welcome—Staff greeted each participating child when they arrived with a smile, asking questions, sharing comments. (8:10 am to 8:13 am, approximately). Staff members noticed that by the second week of The Breakfast Club, students from different classrooms were learning each other’s names, and supporting each other throughout The Breakfast Club with verbal encouragement and peer modeling.

- Strengthening/Core Exercises—The physical therapist began the group in the leadership role, with the occupational therapist supporting exercises via visual supports and modeling, and speech therapist providing verbal cueing/explanation. A dedicated Breakfast Club website (set up via Google Sites) had additional visuals for each strengthening activity. Exercises typically started with core stabilization, then upper body movements and lower body positions. During most days, the physical therapist modeled the activities, with occupational therapist visual support and speech therapist verbal support (8:13 am to 8:21 am, approximately). Classroom teachers supported the students in their classrooms to complete each exercise. Due to the highly consistent nature of these exercises, children showed mastery and engagement, as well as improved endurance as the year progressed.

- Games/Finger Play—Occupational therapist–led preparatory and upper-extremity activities were typically scheduled next. The occupational therapist led the group in 1 to 3 music-and movement songs, such as Head-Shoulders-Knees-Toes, Five Little Monkeys, and the Hokey Pokey song. Sometimes a peer model student would lead the songs, allowing for peer modeling and student leadership. During songs, the physical therapist supported implementation through visual support and occasional clarifications/practice of the movements, while the speech therapist provided feedback and verbal support to students (8:21 am to 8:28 am, approximately).

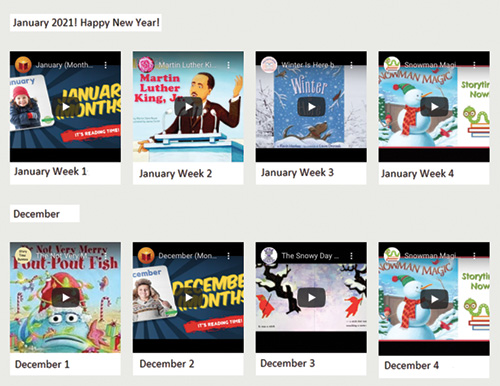

- Reading a Book—The speech therapist then stepped into a leading role, guiding the group by either reading a book (at home with the therapist) or via an online literary resource. The speech therapist supported this activity with vocabulary cards, questions, and objects as visual supports (see Figure 1). The physical therapist often infused movement and yoga positions into the reading, while the occupational therapist provided verbal praise, embedded active student responding opportunities, and provided visual support to the literacy activity (8:28 am to 8:34 am, approximately). Each book was read five times, Monday through Friday of the same week, allowing for repetition and reinforcement of learning. By Friday, the speech therapist was able to review vocabulary with students and probe for retention of new words. Students grew more confident throughout the week, showing pride and excitement in their learning.

- Goodbye—The group sang and waved goodbye, and each student/staff member returning to the scheduled virtual or in-person classroom (8:34 am to 8:35 am, approximately). A clear ending mechanism was incorporated to allow for closure to The Breakfast Club.

Figure 1. Sample Books from the Speech Therapy Portion of The Breakfast Club Home Page

Mid- and Post-Pandemic Lesson Learned: School-Based Interprofessional Collaboration Should Start Small

Ultimately, there were many practical implications from The Breakfast Club project. Yet the primary insight for the team was the importance of intentionally creating a shared and interprofessionally collaborative model of implementation built on doable and feasible steps. The nuts and bolts of pooling our professional knowledge and resources were surprisingly simple. The therapy team created a Google Site together, where we could all add, remove, and modify material at any time. Although each therapist contributed to certain areas pertaining to their profession, maintaining current content, and deciding on learning themes, was decided by the team as a whole. Reeves and colleagues (2018) similarly explain that interdependence and shared responsibility are foundational components of true collaboration. By allowing all therapists to have equal editing rights of the website as well as responsibility for planning and implementation, the team shared the control—and the burden—of planning.

The Google Site was ever changing. We added, removed, or modified components as necessary. The physical therapist would add new exercises or modify a picture if the feedback from parents indicated that would be helpful. The speech therapist uploaded videos, books, and vocabulary cards each week. In the occupational therapy section, games, pictures, and activities were modified based on the curricular themes covered in The Breakfast Club that month. Though each therapist was a primary contributor to certain areas of the site, all team members provided feedback to collaborate on themes, topics, and presentation of skills that related to all therapy areas. This shared responsibility was only possible through clear role delineation, with each therapist understanding their own and each other’s unique roles, as well as intersections between professional roles.

Ultimately, the relatively simple and repetitive implementation of The Breakfast Club supported evidence that interprofessional collaboration, while easier said than done, is more about taking small, actionable steps than creating sophisticated, well-planned agendas (Ward et al., 2017). The Breakfast Club was far from perfect, but it was a small, doable project that yielded tremendous personal and professional results. Had the therapy team waited, planned, researched, and attempted to make it “perfect,” The Breakfast Club may have never started at all. Instead, the team chose to start, make mistakes, forgive themselves, and keep working. The team chose to be creative with available resources to start at a place that was feasible. The Breakfast Club began in September 2020 and continued for the full school year through the last day of school in June 2021. With full-time school resuming in September 2021, the mindset of small, feasible moments of collaboration helped the therapy team maintain collaborative gains, while working on tight schedules. The key lesson was for the team to schedule consistent times each week to co-treat or co-plan. As long as the therapy team consistently collaborates, spending time together to plan and implement initiatives, this is viewed as an interprofessional victory—even when the collaboration or session is not picture perfect.

Ultimately, we learned that interprofessional collaboration is not a destination, it is a journey. Reeves and colleagues (2018) describe ingredients of interprofessional collaboration as including shared identity, defined roles, interdependence, integration, shared responsibilities, and team activities. As a group of planning therapists, we worked hard to create a shared identity and a shared sense of purpose surrounding the goals of The Breakfast Club. The team also worked to delineate roles, responsibilities, and activities. Our interprofessional strengths lay in our ability to work collaboratively as well as interdependently.

So, when school returned to full-time, in-person instruction in September 2021, the therapy team made the intentional decision to continue a virtually delivered Breakfast Club. It may seem surprising that Breakfast Club continued, with the school-wide virtual collaborative groups running once per week, with between 5 and 10 classrooms participating. The team’s hard work on personal role definition has enabled a sustained improvement in shared responsibility, coupled with a deep respect for each other’s scope of practice. Though in-person therapy has resumed, continuing the interprofessional collaboration by leveraging the power of technology allows for therapists and teachers to virtually meet in a single online space at the same consistent time each week.

Conclusion

Through the creation of The Breakfast Club, we learned the value of turning to each other in times of great need. The challenges emerging from this pandemic were so great, and the loneliness, helplessness, and feelings of disconnect too painful to ignore. We learned that our greatest strength was each other. Instead of tackling our problems alone, we learned to double-down on interprofessional opportunities, problem solve together, and listen to each other in ways that we had never done before. Now that our school has reopened for full-time instruction, we have continued to implement a modified Breakfast Club. The flexible delivery has expanded our ability to work with each other across locations, schedules, and competing workloads. Overall, we have learned to harness our relationships, technology, and resourcefulness—and these skills can take us far past the pandemic into years of successful collaboration.

Do what you can, with what you have, where you are—Teddy Roosevelt

References

Giess, S., & Serianni, R. (2018). Interprofessional practice in schools. Perspectives of the ASHA Special Interest Groups, 3(16), 88–94. https://doi.org/10.1044/persp3.SIG16.88

Natale, J. E., Boehmer, J., Blumberg, D. A., Dimitriades, C., Hirose, S., Kair, L. R., ... Lakshminrusimha, S. (2020). Interprofessional/interdisciplinary teamwork during the early COVID-19 pandemic: Experience from a children’s hospital within an academic health center. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 34(5), 682–686. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820.2020.1791809

Reeves, S., Xyrichis, A., & Zwarenstein, M. (2018). Teamwork, collaboration, coordination, and networking: Why we need to distinguish between different types of interprofessional practice. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 32(1), 1–3. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/13561820.2017.1400150

Soler-Gonzalez, J., San-Martín, M., Delgado-Bolton, R., & Vivanco, L. (2017). Human connections and their roles in the occupational well-being of healthcare professionals: A study on loneliness and empathy. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 1475. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01475

Ward, H., Gum, L., Attrill, S., Bramwell, D., Lindemann, I., Lawn, S., & Sweet, L. (2017). Educating for interprofessional practice: Moving from knowing to being, is it the final piece of the puzzle? BMC Medical Education, 17(1), 5. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-016-0844-5

Xyrichis, A., & Williams, U. (2020). Strengthening health system’ response to COVID-19: Interprofessional science rising to the challenge. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 34(5), 577–579. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820.2020.1829037

Zahava L. Friedman, PhD, OT, BCBA, is an Assistant Professor at the Department of Occupational Therapy at Kean University. Areas of teaching and research focus include pediatric occupational therapy practice and building interprofessional and community-based partnerships.

The author thanks Dr. Chris Lanni, DPT, and Ms. Maureen Casey for their collaboration, and all teachers and families who participated in the initial Breakfast Club throughout school year 2020–2021.