Role of occupational therapy in comprehensive integrative pain management

Jointly commissioned by:

Introduction

Pain is the top reason given for seeking health care.1 People with acute and chronic pain face significant challenges accessing and understanding which facets of person-centered, multimodal, comprehensive integrative pain management (CIPM) would provide improvement in functional capacity, pain interference, quality of life, and pain management coping skills. Most clinical guidelines recommend non-pharmacological and integrative therapies as first-line interventions for pain, and the Health & Human Services Inter-Agency Pain Management Best Practices Task Force Report presents a convincing roadmap for advancing best practices in multidisciplinary, whole-person care.2 This approach includes traditional and advancing medication and interventional procedures, complementary and integrative services, restorative therapies, and behavioral health approaches. The purpose of this collaborative effort between AACIPM and AOTA is to build awareness across stakeholders by providing additional context about occupational therapy as an important part of a quality interdisciplinary and integrative team.

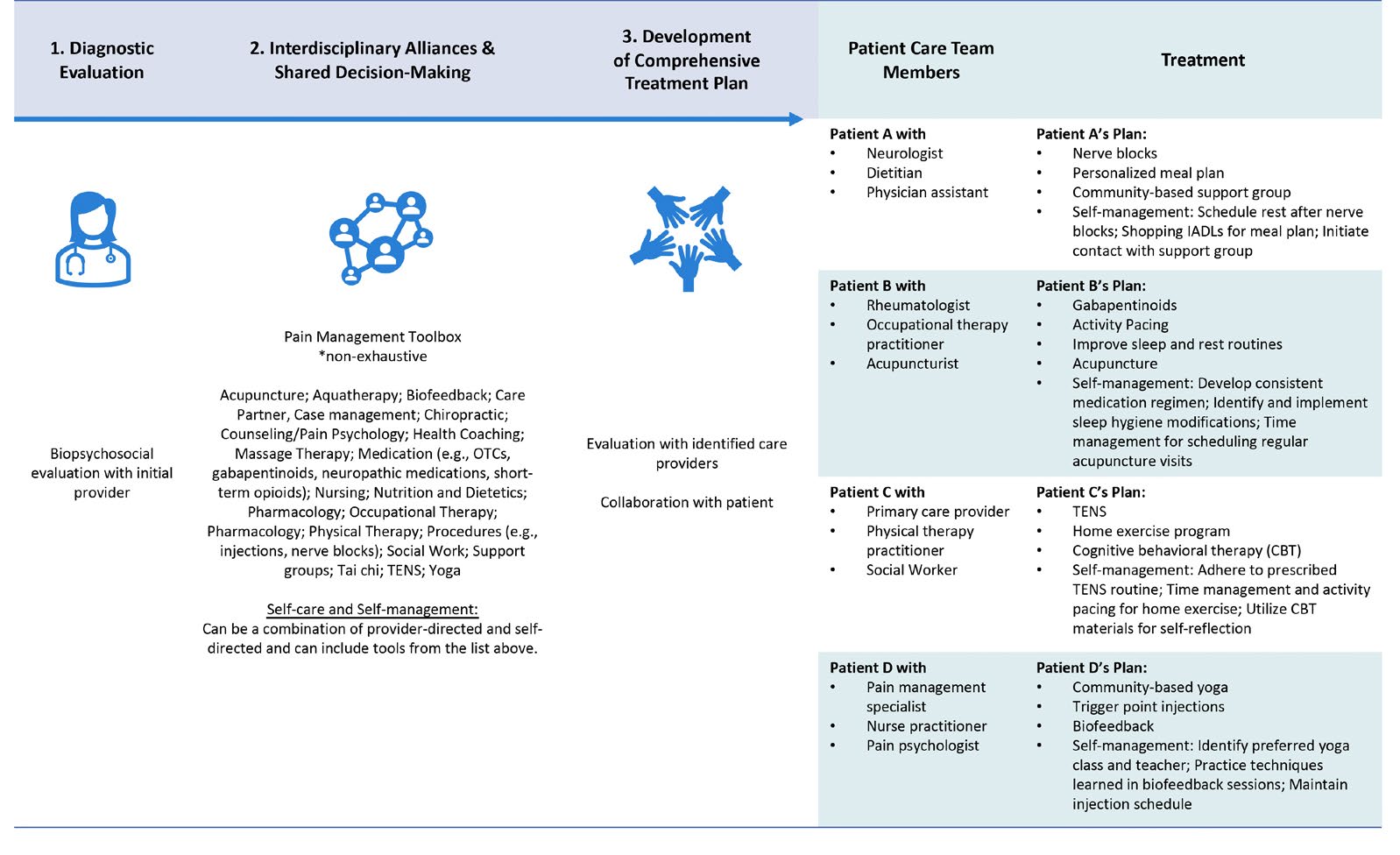

Image 1 highlights examples of comprehensive treatment plans that can result from interdisciplinary collaboration, where all disciplines are considered and integrated appropriately. Self-management is included within each patient’s treatment plan to highlight the importance of patient engagement and to show how each team member can play a role in facilitating self-management. While some patients enter care teams with strong self-management skills, others may need additional training and intervention to develop this invaluable skillset. As noted in Table 1, occupational therapy practitioners can play a significant role in training patients to increase their confidence in their health management and IADLs, including symptom and condition management, communication with their health care system staff, medication management, and building health-promoting daily routines.3 Each individual will have different self-management needs, which is why an individualized, evidence-based, multimodal approach is considered the best practice in pain care.

Image 1. Diagnostic Process and Treatment Examples From an Interdisciplinary Approach to Pain Management

Adapted from: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2019, May). Pain Management Best Practices Inter-Agency Task Force

Report: Updates, Gaps, Inconsistencies, and Recommendations. https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/pmtf-final-report-2019-05-23.pdf46

A Person With Complex Regional Pain Syndrome: A Case Study

Mark is a 53-year-old male high school teacher with a diagnosis of complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS) Type 1 bilaterally in his hands caused by a repetitive strain injury at work. His pain management doctor prescribed neuralgia medications (Gabapentin, Ketamine, and Mirtazapine) and educated him about additional interventional and non-pharmacological treatment options for CRPS including sympathetic nerve blocks, spinal cord or dorsal root ganglion nerve stimulators, occupational therapy, physical therapy, and pain psychology. After reviewing his treatment options and insurance coverage for these recommended treatments, Mark participated in occupational therapy, physical therapy, and pain psychology as part of an interdisciplinary team approach.

Mark took a temporary leave of absence from work when he was diagnosed with CRPS due to his inability to perform his essential job functions. He utilized this time to participate in the interdisciplinary pain management program. At the initial occupational therapy evaluation, Mark reported symptoms of aching and shooting pain, sensitivity to touch, and occasional edema. Mark identified fine motor movements, driving, and stress as pain triggers, and he identified the use of deep pressure as a pain alleviating factor. Mark’s primary functional complaint was pain flares that interfered with work-related productivity, most frequently caused by the compounding effect of stress combined with repetitive or sustained fine motor use (e.g., handling papers, handwriting, and typing). He also was unable to participate in avocation and leisure activities, including playing the piano and transcribing a book he wrote into another language. Additionally, his pain negatively impacted his mood and caused interpersonal challenges with his partner, as he would avoid participating in social and community activities with her.

In collaboration with Mark, the following occupational therapy goals were identified: improve tolerance for fine motor activities in order to return to work, establish new health-promoting stress management strategies and routines, gradually resume participation in preferred avocation activities without triggering a CRPS pain flare up, and explore new activities he can tolerate and engage in with his partner.

Mark had a PPO insurance plan that included occupational therapy, physical therapy, and pain psychology coverage, based on medical necessity with a $30 copayment for each discipline. He was seen for a total of 12 occupational therapy sessions before he met his occupational therapy goals and was discharged. Occupational therapy visits started at a frequency of once every 2 weeks, then gradually decreased in frequency as Mark became more independent with his pain self-management. Mark’s treatment and functional outcomes are summarized below:

- Patient education regarding pain physiology, trigger identification, and symptom management and tracking.

- Activity pacing and energy conservation strategies to avoid over activity during fine motor tasks, to reduce frequency and intensity of symptom flare ups. This included a graded activity plan to gradually increase tolerance for written grading tasks from 5 minutes to 30 minutes with rest breaks. This approach was also used to gradually increase participation in piano playing from 0x/week to 3x/week.

- Advocacy and self-advocacy strategies to identify workplace accommodations that eventually allowed Mark to return to work. With the use of new ergonomic and adaptive equipment, including talk-to-text software and a foot mouse to reduce fine motor demands, and the incorporation of a teaching assistant to offload fine motor tasks, Mark was able to return to full time work.

- Self-regulation and stress management training, including mindfulness and adaptive thinking strategies, to decrease stress while driving and teaching and to improve management of pain.

- Reintegrating into outdoor exercise routines with his partner by going on weekend hikes, to alleviate stress and to reduce fear avoidance behaviors and risk for social isolation.

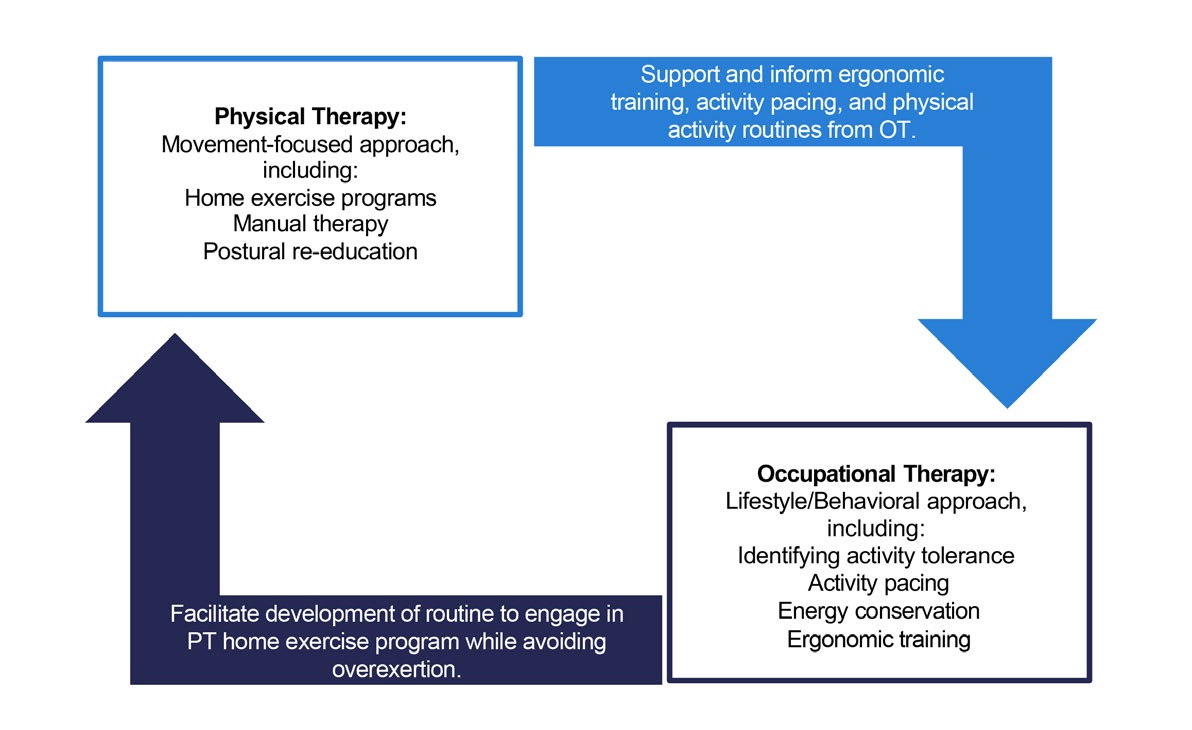

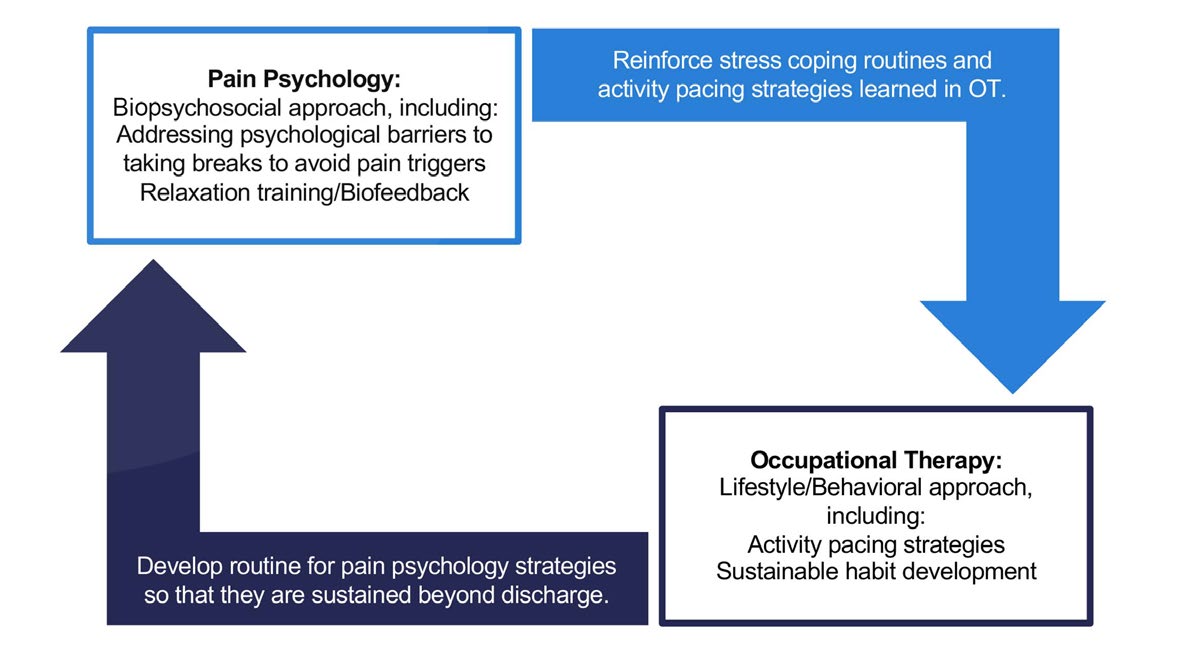

Mark’s recovery process and outcomes achieved were the direct benefit of an interdisciplinary pain management team, as each discipline positively reinforced the treatment plan and patient goals communicated by the other providers. Images 2 and 3 demonstrate the different treatment modalities used in occupational therapy, physical therapy, and pain psychology and how the integrative team approach is used to support each discipline’s goals to enhance and progress treatment outcomes.

Image 2. Synergistic Interdisciplinary Team Between Physical Therapy and Occupational Therapy to Treat Mark

Image 3. Synergistic Interdisciplinary Team Approach Between Pain Psychology and Occupational Therapy to Treat Mark

Case Study—At a Glance

|

Client Factors |

|

|

Occupational Therapy Insurance Coverage and Plan of Care |

|

|

Occupational Therapy Treatment Plan |

|

|

Integrative Pain Management Providers Included in Treatment |

|

|

Functional Outcomes |

|

Conclusion

Pain is complex and requires a person-centered, multimodal, interdisciplinary approach to care. A best practice involves a team of providers working synergistically and with patient shared decision making so that individuals are able to achieve what matters to them. Occupational therapy practitioners have an important role on an individual’s pain management team. With their training, occupational therapy practitioners provide unique, individualized interventions focused on nonpharmacological self-management and increasing a patient’s functional and meaningful participation in their life.47 While occupational therapy practitioners offer their distinctive lens on a comprehensive team, they are also effective and engaged collaborators, which improves the patient’s quality of care through the compounding benefits of a synergistic treatment plan. Moving forward, action steps must be taken to increase patient, payer, and provider awareness of occupational therapy’s role, and to address inequities in the health care system in order to optimize the care that occupational therapy practitioners can provide. Occupational therapy’s presence on a comprehensive pain management team is a vital factor in providing exceptional, holistic patient care.

The Alliance to Advance Comprehensive Integrative Pain Management (AACIPM) is the first-of-its-kind multi-stakeholder collaborative, comprised of people living with pain, public and private insurers, government agencies, patient and caregiver advocates, researchers, purchasers of healthcare, policy experts, and the spectrum of healthcare providers involved in the delivery of comprehensive integrative pain management.

The American Occupational Therapy Association is the national professional association representing the interests of more than 220,000 occupational therapists, occupational therapy assistants, and students of occupational therapy. The science-driven, evidence-based practice of occupational therapy enables people of all ages to live life to its fullest by promoting health and minimizing the functional effects of chronic diseases, illness, injury, and disability. AOTA believes that understanding a person’s whole health, including function, environment, and context are crucial.

References

1National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health. (2021, September 22). Pain. https://www.nccih.nih.gov/health/pain

2Department of Health and Human Services. (2019). Department of health and human services pain management best practices inter-agency task force report. https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/pmtf-final-report-2019-05-23.pdf

3American Occupational Therapy Association. (2020). Occupational therapy practice framework: Domain and process (4th ed.). American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 74(Suppl. 2), 1-87. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2020.74S2001

4American Occupational Therapy Association. (n.d.). About occupational therapy: What is occupational therapy? https://www.aota.org/about/for-the-media/about-occupational-therapy

5Rogers, A. T., Bai, G., Lavin, R. A., & Anderson, G. F. (2016, September 2). Higher hospital spending on occupational therapy is associated with lower readmission rates. Medical Care Research and Review, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077558716666981

6Oslund, S., Robinson, R. C., Clark, T. C., Garofalo, J. P., Behnk, P. Walker, B., … & Noe, C. E. (2009, July). Long-term effectiveness of a comprehensive pain management program: strengthening the case for interdisciplinary care. Baylor University Medical Center Proceedings, 22(3), 211–214.

7Breeden, K. L. (2011). Opioid guidelines and their implications for occupational therapy. Medicine, 1.

8Farmer, P. K., Snodgrass, S. J., Buxton, A. J., & Rivett, D. A. (2015). An investigation of cervical spinal posture in cervicogenic headache. Physical therapy, 95(2), 212–222.

9Mongini, F., Ciccone, G., Rota, E., Ferrero, L., Ugolini, A., Evangelista, A., ... & Galassi, C. (2008). Effectiveness of an educational and physical programme in reducing headache, neck and shoulder pain: A workplace controlled trial. Cephalalgia, 28(5), 541–552.

10Watson, D. H., & Drummond, P. D. (2012). Head pain referral during examination of the neck in migraine and tension-type headache. Headache: The Journal of Head and Face Pain, 52(8), 1226–1235.

11American Occupational Therapy Association. (2015). Take a stand to prevent falls: Falls prevention presentation developed by AOTA and AGPT, a component of APTA. https://www.aota.org/-/media/corporate/files/practice/aging/falls/prevent-falls-aota-apta.pptx

12Mathiowetz, V. G., Matuska, K. M., Finlayson, M. L., Luo, P., & Chen, H. Y. (2007). One-year follow-up to a randomized controlled trial of an energy conservation course for persons with multiple sclerosis. International Journal of Rehabilitation Research, 30(4), 305–313.

13McLean, A., Coutts, K., & Becker, W. J. (2012). Pacing as a treatment modality in migraine and tension-type headache. Disability and Rehabilitation, 34(7), 611–618.

14Nielson, W. R., Jensen, M. P., Karsdorp, P. A., & Vlaeyen, J. W. (2013). Activity pacing in chronic pain: concepts, evidence, and future directions. Clinical Journal of Pain, 29(5), 461–468.

15Sauter, C., Zebenholzer, K., Hisakawa, J., Zeitlhofer, J., & Vass, K. (2008). A longitudinal study on effects of a six-week course for energy conservation for multiple sclerosis patients. Multiple Sclerosis Journal, 14(4), 500–505.

16Stensland, M., & Sanders, S. (2018). Living a life full of pain: Older pain clinic patients’ experience of living with chronic low back pain. Qualitative Health Research, 28(9), 1434–1448.

17Barlow, J., Wright, C., Sheasby, J., Turner, A., & Hainsworth, J. (2002). Self-management approaches for people with chronic conditions: a review. Patient Education and Counseling, 48(2), 177–187.

18Buse, D. C., & Andrasik, F. (2009). Behavioral medicine for migraine. Neurologic Clinics, 27(2), 445–465.

19Alberti, R. E., & Emmons, M. L. (2008). Your perfect right: Assertiveness and equality in your life and relationships (9th ed.). Impact Publishing.

20Buse, D. C., Rupnow, M. F., & Lipton, R. B. (2009, May). Assessing and managing all aspects of migraine: Migraine attacks, migraine-related functional impairment, common comorbidities, and quality of life. Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 84(5), 422–435).

21Caudill, M. A. (2008). Managing pain before it manages you (3rd ed.). Guilford Press

22Lauwerier, E., Paemeleire, K., Van Damme, S., Goubert, L., & Crombez, G. (2011). Medication use in patients with migraine and medication-overuse headache: The role of problem-solving and attitudes about pain medication. Pain, 152(6), 1334–1339.

23Ehde, D. M., Dillworth, T. M., & Turner, J. A. (2014). Cognitive-behavioral therapy for individuals with chronic pain: Efficacy, innovations, and directions for research. The American Psychologist, 69(2), 153–166. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0035747.

24Greeson, J. & Eisenlohr-Moul, T. (2014). Mindfulness-based stress reduction for chronic pain. In R. A. Baer (Ed.), Mindfulness-based treatment approaches (2nd ed.; pp. 269–292). Elsevier, Inc. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-416031-6.00012-8.

25Buchholz, D. (2002). Heal your headache: The 1-2-3 program for taking charge of your pain. Workman Publishing.

26Okifuji, A., Donaldson, G. W., Barck, L., & Fine, P. G. (2010). Relationship between fibromyalgia and obesity in pain, function, mood, and sleep. The Journal of Pain, 11, 1329–1337.

27Brosseau, L., Wells, G. A., Pugh, A. G., Smith, C. A., Rahman, P., Àlvarez Gallardo, I. C., ... Taki, J. (2016). Ottawa panel evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for therapeutic exercise in the management of hip osteoarthritis. Clinical Rehabilitation, 30, 935–946.

28Hester, J., & Tang, N. K. (2008). Insomnia co-occurring with chronic pain: Clinical features, interaction, assessments and possible interventions. Reviews in Pain, 2(1), 2–7.

29Straube, S., & Heesen, M. (2015). Pain and sleep. PAIN, 156, 1371–1372.

30Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 EEOC Enforcement Guidance on Reasonable Accommodation and Undue Hardship Under the Americans with Disabilities Act http://www.eeoc.gov/policy/docs/accommodation.html#requesting.

31U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2016). 2015 nonfatal occupational injuries and illnesses: Cases with days away from work: Case and demographics. https://stats.bls.gov/iif/oshwc/osh/case/osch0058.pdf

32Kinnersley, P., Edwards, A., Hood, K., Cadbury, N., Ryan, R., Prout, H., … Butler, C. (2007). Interventions before consultations for helping patients address their information needs. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 3, CD004565.

33Linton, S. J., Boersma, K., Traczyk, M., Shaw, W., & Nicholas, M. (2016). Early workplace communication and problem solving to prevent back disability: Results of a randomized controlled trial among high-risk workers and their supervisors. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation, 26(2), 150–159.

34Mosen, D. M., Schmittdiel, J., Hibbard, J., Sobel, D., Remmers, C., & Bellows, J. (2007). Is patient activation associated with outcomes of care for adults with chronic conditions? Journal of Ambulatory Care Management, 30(1), 21–29.

35Engel-Yeger, B., & Dunn, W. (2011). Relationship between pain catastrophizing level and sensory processing patterns in typical adults. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 65, e1–e10. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2011.90004

36National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine. (2019). The role of nonpharmacological approaches to Pain Management: Proceedings of a workshop. Washington, DC: The National Academies Pres.

37Elton, D. (2020). Data about access to pain therapies based on zip code [PowerPoint Slides]. AACIPM Symposium: Equity in Access to Pain Management for People with Chronic Pain. https://painmanagementalliance.org/wp/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/Equity-in-Access-Symposium-Data-about-Access-to-Pain-Therapies-Based-on-Zip-Code-9-24-20.pdf

38U.S. Pain Foundation. (2021). Understanding barriers to multidisciplinary pain care. https://uspainfoundation.org/surveyreports/accesstocare/.

39Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. (2021, January 7). COVID-19 frequently asked questions (FAQs) on Medicare fee-for-service (FFS) billing. P. 65. https://edit.cms.gov/files/document/medicare-telehealth-frequently-asked-questions-faqs-31720.pdf

40Pronovost, A., Peng, P., & Kern, R. (2009). Telemedicine in the management of chronic pain: A cost analysis study. Canadian Journal of Anesthesia/Journal Canadien d’Anesthésie, 56(8), 590–596.

41Gellatly, J., Pelikan, G., Wilson, P., Woodward-Nutt, K., Spence, M., Jones, A., & Lovell, K. (2018). A qualitative study of professional stakeholders’ perceptions about the implementation of a stepped care pain platform for people experiencing chronic widespread pain. BMC Family Practice, 19(1), 1–11.

42Grogan-Johnson, S., Alvares, R., Rowan, L., & Creaghead, N. (2010). A pilot study comparing the effectiveness of speech language therapy provided by telemedicine with conventional on-site therapy. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare, 16(3), 134–139.

43Levy, C. E., Geiss, M., & David Omura DPT, M. H. A. (2015). Effects of physical therapy delivery via home video telerehabilitation on functional and health-related quality of life outcomes. Journal of Rehabilitation Research and Development, 52(3), 361.

44Sangelaji, B., Smith, C., Paul, L., Treharne, G., & Hale, L. (2017). Promoting physical activity engagement for people with multiple sclerosis living in rural settings: A proof-of-concept case study. European Journal of Physiotherapy, 19(suppl. 1), 17–21.

45Harkey, L. C., Jung, S. M., Newton, E. R., & Patterson, A. (2020). Patient satisfaction with telehealth in rural settings: A systematic review. International Journal of Telerehabilitation, 12(2), 53–64.

46U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2019, May). Pain management best practices inter-agency task force report: Updates, gaps, inconsistencies, and recommendations. https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/pmtf-final-report-2019-05-23.pdf

47American Occupational Therapy Association. (2021). Position Statement-Role of occupational therapy in pain management. American Journal of Occupational Therapy. https://research.aota.org/ajot/article/75/Supplement_3/7513410010/23131/Role-of-Occupational-Therapy-in-Pain-Management?msclkid=85f57ce8ba8911ec8aa76f0a7e22a723