Intergenerational programming for grandparent-grandchild dyads: Practical applications for OT professionals

Child and grandmother enjoy a game of ‘balloon bat’ as they coordinate passing a balloon back and forth without letting it touch the ground.

There are approximately 55 million adults aged 65 years and older in the United States, a number that is expected to rise to 70 million by 2030 (AARP, 2014). One of the challenges experienced by this rapidly growing age group is that older adults are becoming increasingly separated from younger generations. This separation is largely due to decreased opportunities for co-habitation, reduced intergenerational social engagement including shared leisure and recreational pursuits, and negatively skewed attitudes and beliefs on aging or ageism (Kaplan, 2001; Neyfakh, 2014). The observed “age segregation” can lead to broad, negative generational effects at personal, familial, and societal levels. Specifically, age segregation minimizes chances for generations to share knowledge, develop mutual understanding and compassion, and mitigate social isolation and loneliness experienced by older adults (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2016). The COVID-19 pandemic has further aggravated social isolation for older adults, which is linked to increased likelihood of developing depression and anxiety symptoms, hypertension and other cardiovascular diseases, and cognitive decline (Morrow-Howell et al., 2020). To combat the negative effects of age segregation and social isolation experienced by older adults, the CDC (2016) recommends increased advocacy, education, and training opportunities for intergenerational programming.

Intergenerational Programming

Intergenerational programming is defined as “activities or programs that increase cooperation, interaction, or exchange between any two generations” that involve “the sharing of skills, knowledge, or experience between old and young” (Thorp, 1985, p. 3). Intergenerational programming can not only combat age segregation and social isolation for older adults, but it can also cultivate intergenerational relationships, community inclusion, and participation in meaningful activities across the lifespan (DeVore et al., 2016; Kaplan, 1994; Statham, 2009). Within the context of occupational therapy (OT) practice, intergenerational programming supports participation in co-occupations by members from different generations, allowing for shared physical, emotional, and volitional engagement and concurrent participation in meaningful occupations (Ono et al., 2014). This article describes a novel intergenerational program, entitled “Grandpa/Grandma and Me,” designed and pilot tested by a team of geriatric and pediatric OT experts in partnership with an outpatient pediatric clinic, Amy Rogge & Associates (ARA). The two-fold aim of this program was to (1) facilitate engagement in intergenerational roles and relationships, and (2) support the development and preservation of gross motor skills to improve leisure participation and overall quality of life for child and older adult dyads.

Grandmother and child participate in a relationship building activity together. Grandmother listens as child explains her drawing.

“Grandpa/Grandma and Me” Occupational Therapy Program

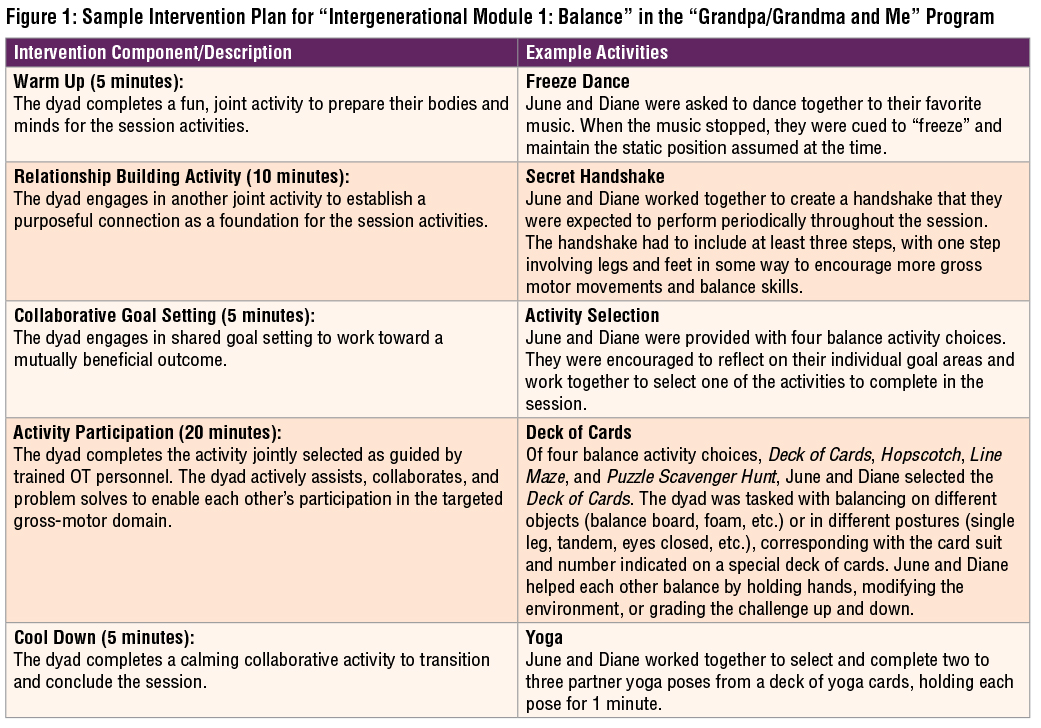

The “Grandpa/Grandma and Me” curriculum was created from three distinct phases: (1) completing a literature review, (2) conducting joint research team meetings with geriatric and pediatric OT experts to establish initial constructs, and (3) generating a structured intergenerational curriculum. The curriculum featured six intergenerational modules, each targeting a unique gross motor domain (e.g., balance, body awareness, core stabilization). The intervention format was composed of five distinct components: Warm Up, Relationship Building Activity, Collaborative Goal Setting, Activity Participation, and Cool Down (see Figure 1 for a sample intervention plan from the balance module). For the purpose of piloting the program, a child and grandparent dyad who satisfied the predetermined eligibility criteria was purposively selected. To enroll in the program, the child and grandparent had to be biologically related, both present with mild to moderate gross motor deficits as verified during the initial screening, interview, and pre-assessment; and both be without severe cognitive, language, and motor deficits that may have led to safety risks.

Case Example: June and Diane

June, a typically developing 5 ½ year old, attended the “Grandma and Me Program” with her grandmother, Diane, a 60-year-old full-time caregiver. Although June’s medical history was unremarkable, June’s parents reported concerns related to her coordination, attention, and general sequencing of tasks. Diane, on the other hand, presented with a history of falls and hypertension and arthritis that were well-managed at the time of enrollment; she also reported maintaining a sedentary lifestyle with minimal social engagement opportunities.

After the initial screening and interview, the dyad completed the following pre-intervention measures: June completed the Bruininks-Oseretsky Test of Motor Proficiency, Second Edition (BOT-2; Deitz et al., 2007); Diane completed the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS; Kurlowicz & Sherry, 2007) and Timed Up and Go (TUG; Kear et al., 2016). The dyad also answered a series of open-ended questions related to perceptions on intergenerational relationships, such as “What do you like to do with your grandparent/grandchild?” and “Do you feel close to your grandparent/grandchild?”

The pilot dyad participated in 45-minute sessions, 1 time per week for 6 weeks, to complete the 6 intergenerational modules targeting various gross motor domains. The layout of the 45-minute session completed by June and Diane during “Intergenerational Module 1: Balance” is described in Figure 1. Throughout the session, a coaching approach was applied so that June and Diane were empowered to guide each other through the selected activity. To encourage further connection between June and Diane, the session also emphasized immersion in relationship building themes such as teamwork, shared humor and reminiscence, and skill sharing. For example, when engaging in the game of Hopscotch, Diane was encouraged to share how she used to play this game when she was young. In the process of helping Diane to complete the balance activity, June also engaged in various static and dynamic gross-motor movements in a meaningful and purposeful way.

At the conclusion of the six intergenerational sessions, June displayed a 32.9% improvement across all motor areas of the BOT-2, including all gross and fine motor subsections, increasing her total motor composite score from 152, indicating below average performance, to 202, indicating average performance. When asked about her relationship with Diane post-programming, June stated, “I feel happy about my grandma, but sad that this is our last session together,” indicating overall enjoyment in participating in the program. June also expressed increased feelings of closeness and comfort with Diane, which transferred to her improved confidence in talking with other older adults as reported on her post-intervention open-ended questionnaire. Diane improved by 50.0% on the GDS from a score of 6 to a score of 3 (a score of 5 or more suggests depression), indicating that she was no longer experiencing depression symptoms. She also improved by 33.2% on the TUG (from 6.38 seconds to 4.26 seconds—greater than or equal to 12 seconds indicates a high fall risk), indicating improvements in her balance and agility. Diane reported feelings of connection and acceptance, and improved balance when completing her ADLs and IADLs. Diane also expressed increased motivation, life satisfaction, re-engagement in activities of interest, sense of self-worth, and intergenerational relationship with June as reported on her post-intervention open-ended questionnaire.

Implications/Recommendations for Occupational Therapy

Intergenerational programming, like the “Grandpa/Grandma and Me” curriculum, has the potential to positively impact individuals across the lifespan, increasing their participation in meaningful occupations, roles, and relationships.

Application to Pediatric Practice

In pediatric practice, OT practitioners can consider implementing parts of the “Grandpa/Grandma and Me” curriculum. If a client’s older adult caregiver is available to be part of an OT session, he or she can be invited to participate in “Warm Up” or “Relationship Building Activity” as a cheerleader, aide, and/or facilitator as opposed to sitting in a waiting room or visiting at the end of the session. These activities can be designed to target cognition, fine-motor skills, and social participation that can be mutually beneficial for the dyad. If there is no availability of an older adult caregiver for an OT session, home program activities that promote intergenerational relationship and interactions such as collaborating on a novel baking recipe, working on a collage with family photos to practice using adaptive scissor skills, and practicing a chair dance routine with a grandparent can be explored.

Application to Geriatric Practice

Similarly, in geriatric practice, OT practitioners can incorporate parts of the “Grandpa/Grandma and Me” curriculum with modifications in their everyday practice. For example, in a skilled nursing facility setting, OT practitioners can consider completing the curriculum as a monthly event where older adults are invited to bring their grandchildren or alternatively, interact with school-aged children in partnership with a community organization. In a general outpatient rehabilitation setting, pediatric and older adult clients can participate in shared leisure activities such as gardening and board games. OT practitioners can also use these intergenerational principles to assist older adults and their grandchild to participate in activities that require executive functioning or motor skills via telehealth. See Figure 2 for further considerations and implications for OT practice.

Conclusion

As a profession founded on the belief that participating in meaningful occupations, roles, and relationships leads to greater health outcomes and well-being, OT practitioners are well suited to design, lead, and incorporate intergenerational activities into their everyday practices. The “Grandpa/Grandma and Me” program suggests an approach to integrate intergenerational concepts as therapeutic mechanisms for both geriatric and pediatric populations—toward a positive cultural change in the inclusion of all individuals, regardless of age.

Child and grandmother learn and perform "The Macarena" dance to address skills related to bilateral coordination, balance, memory, and crossing midline.

Child and grandmother participate in three-legged race to address skills related to coordination, balance, body awareness, and problem solving.

References

AARP. (2014). Baby boomer facts and figures. https://www.aarp.org/livable-communities/info-2014/livable-communities-facts-and-figures.html#:~:text=The%20number%20of%20people%2065%20and%20older%20in,double%20from%2037%20million%20to%2071.5%20million%20people.%29

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2016, November). Healthy aging in action: Advancing the national prevention strategy. https://www.cdc.gov/aging/pdf/healthy-aging-in-action508.pdf

DeVore, S., Winchell, B. & Rowe, J. M. (2016, April 26). Intergenerational programming for young children and older adults: An overview of needs, approaches, and outcomes in the United States. Childhood Education, 92(3), 216–225. https://doi.org/10.1080/00094056.2016.1180895

Deitz, J. C., Kartin, D., & Kopp, K. (2007). Review of the Bruininks-Oseretsky Test of Motor Proficiency, Second Edition (BOT-2). Physical & Occupational Therapy in Pediatrics, 27(4), 87–102. https://doi.org/10.1080/J006v27n04_06

Kaplan, M. (1994). Promoting community education and action through intergenerational programming. Children’s Environments, 11(1), 48–60. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41514906

Kaplan, M. (2001, January 5). Some what’s and why’s of intergenerational programming. PennState College of Agricultural Sciences: Department of Agricultural Economics, Sociology, and Education. https://aese.psu.edu/outreach/intergenerational/curricula-and-activities/handouts/factsheets/some-whats-and-whys-of-intergenerational-programming#:~:text=Intergenerational%20programming%2C%22%20as%20defined%20by,sharing%20of%20skills%2C%20knowledge%20or

Kear, B. M., Guck, T. P., & McGaha, A. L. (2016). Timed Up and Go (TUG) test: Normative reference values for ages 20 to 59 years and relationships with physical and mental health risk factors. Journal of Primary Care & Community Health, 8(1), 9–13. https://doi.org/10.1177/2150131916659282

Kurlowicz, L., & Sherry, G. (2007). The Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS). American Journal of Nursing, 107(10). 67–68. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.NAJ.0000292207.37066.2f

Morrow-Howell, N., Galucia, N., & Swinford, E. (2020). Recovering from the COVID-19 pandemic: A focus on older adults. Journal of Aging & Social Policy, 32(4–5), 526–535. https://doi.org/10.1080/08959420.2020.1759758

Neyfakh, L. (2014, August 31). What ‘age segregation’ does to America. Boston Globe. https://www.bostonglobe.com/ideas/2014/08/30/what-age-segregation-does-america/o568E8xoAQ7VG6F4grjLxH/story.html

Ono, K., Kanayama, Y., Iwata, M., & Yabuwaki, K. (2014). Views on co-occupation between elderly persons with dementia and family. Journal of Gerontology and Geriatric Research, 3, 185. https://doi.org/10.4172/2167-7182.1000185

Statham, E. (2009). Promoting intergenerational programmes: Where is the evidence to inform policy and practice? Evidence & Policy: A Journal of Research, Debate and Practice, 5(4). https://doi.org/10.1332/174426409X478798

Thorp, K., (1985). Intergenerational programs: A resource for community renewal. Wisconsin Positive Youth Development Initiative, Inc.

Kasey Harmon, OTD, is a recent Doctor of Occupational Therapy graduate from Creighton University’s Colorado Hybrid Pathway in Denver.

Julia Shin, EdD, OTR/L, is an Assistant Professor and Academic Clinical Education Coordinator in the Department of Occupational Therapy at Creighton University in Omaha, NE.

Amy Rogge, OTD, OTR/L, is the founder and owner of Amy Rogge & Associates, a pediatric occupational therapy practice in Denver, CO, and Special Faculty at Creighton University’s Regis Pathway.

Jenny Junker, OTD, OTR/L, LSVT-BIG, is co-owner of Thrive! Therapy, a mobile outpatient occupational therapy clinic for seniors in Parker, CO, and Special Faculty at Creighton University’s Regis Pathway.

Kylie Sleeth, OTR/L, MS, CLIPP, is co-owner of Thrive! Therapy, a mobile outpatient occupational therapy clinic for seniors in Parker, CO, Lab Assistant at Creighton University’s Regis Pathway, and Professional Development and Education Chair for the Occupational Therapy Association of Colorado.