A recipe for session success: Promoting OT through Universal Design for Learning and text analysis

Occupational therapy practitioners (OTPs) frequently work with clients who face communication and participation challenges. Universal design for learning (UDL) principles and text-analysis tools can help clients navigate situations where effective communication is essential. This article describes how text analysis and UDL concepts are successfully embedded in the creation and curriculum design of our therapy team’s program: Planning for Autism in Communities and Schools, which aims to meet the needs of young adults, age 14 and older, with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) through a sustainable approach to promoting participation.

Universal Design for Learning (UDL)

Universal design (UD) is an overarching framework outlining parameters for ensuring inclusive access to physical environments and technological products. In contrast, UDL addresses inclusive educational material development and application in an instructional environment. The UDL framework optimizes teaching and learning for people with many levels of ability (CAST, Inc., 2021). UDL conceptually facilitates inclusion and participation for clients with communication differences, including literacy levels, preferred languages, and cultural practices. UDL principles contribute to better accessibility and community participation, which can help to mitigate social injustices (CAST, Inc., 2021). See Figure 1 for a comparison of UD and UDL.

The three pillars of UDL provide multiple means of engagement, representation, and action and expression (CAST, Inc., 2021). The engagement pillar encourages learner-centered, self-driven engagement and participation in school and community settings. For our community participation program, we conceptualize engagement as young adults becoming more self-aware and identifying how they want to be a part of community life. The representation pillar involves cultivating a variety of pathways to self expression to meet their sensory, communication, and social needs. We identify the action and expression pillar of UDL as helping clients develop ways to express feelings, needs, and desires to others as a component of their emerging self-advocacy (Fletcher et al., 2021).

McMahon and Walker (2019) cite the definition of UDL in the Higher Education Opportunity Act of 2008 as a framework for guiding educational practices that provide flexibility and reduce barriers. UDL promotes presenting information in a variety of ways; helping clients demonstrate their knowledge and skills in multiple ways; and reducing instructional barriers with educational accommodations while maintaining high achievement standards for students—including those with disabilities or limited English proficiency (CAST, Inc., 2021).

When UDL-designed supports are implemented and incorporated in clinical, educational, and community settings, individuals with and without disabilities encounter more inclusive opportunities for communication and participation (Fletcher et al., 2021). Rutherford and colleagues (2020) championed using family-friendly information and signposting, the practice of encouraging uniformity across environments using symbol sets as vital components of a visual support model. Visual supports in mainstream education can help children who typically need additional support become more able to engage in all activities (Baxter et al., 2015). As a side benefit, when these tools promote understanding and immersion in the environment, they can lead to greater individual independence to engage in their environment.

With the concepts of inclusion and consistency to promote participation in mind, OTPs can encourage early incorporation of augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) devices to facilitate verbal and nonverbal communication and support interactional involvement for clients with communication differences (Saunders, 2018). Hayes and colleagues (2010) discussed the empowerment inherent in the use of visual supports as enabling direct or scaffolded communication between an individual with ASD and others. To support consistent communication, our therapy team subscribes to a web-based graphic software program to meet the needs of clients desiring visual support or using AAC devices.

Current neurodivergent rhetoric advocates for inclusion and embracing differences rather than “curing” them (Saunders, 2018). UDL embraces differences and encourages accessibility for all, rather than making changes for a small number of people, a practice that highlights differences and can have the unintended effect of a person becoming more excluded and separated instead of participating more fully (Saunders, 2018).

Text Analysis

A basic understanding of reading levels and how to adjust them can become an essential skill for OTPs across all settings and can directly impact communication and participation for both clients and families. A client’s reading comprehension level can be screened during the initial interview as part of the occupational profile. Adjusting materials to the client’s reading level helps situate them in their least restrictive environment, and understanding reading levels helps OTPs work with clients and their individual client factors versus using language that must be explained to them.

State Departments of Education and school districts often subscribe to reading-measurement services and report this quantitative data on standardized tests and monthly learner assessments (MetaMetrics, Inc., 2020). Identification of a learner’s unique score, and knowledge of what it represents, can assist OTPs in providing clients with appropriate educational materials, improving accessibility and comprehension.

In addition, several web-based programs exist to measure text and reading comprehension levels (See Table 1). Determining text complexity requires uploading a couple of sentences of text to the program’s analysis tool, retrieving a complexity level or score, and then grading the text based on the factors evaluated by the program for determining complexity. Table 1 outlines four text-analysis programs for determining text complexity and the factors considered for grading text accordingly.

Table 1. Examples of Text-Analysis Tools |

|||

|

Metric(s) |

Text level measurement |

Factors used to determine level |

Web address |

|

Lexile Analyzer* |

Numerical score based on developmental comprehension |

|

|

|

Advantage/TASA Open Standard (ATOS) |

Grade-level based score |

Text complexity: word length, word difficulty, sentence length |

https://www.renaissance.com/products/accelerated-reader/atos-and-text-complexity/ |

|

Degrees of Reading Power: DRP Analyzer |

Aligned to grade-level entry and exit scores; DRP text-difficulty score |

|

|

|

Lumos Text Complexity Analyzer |

Readability score |

|

https://www.lumoslearning.com/llwp/free-text-complexity-analysis.html |

|

*Requires an annual membership of $17.99 USD/year + state tax |

|||

Rutherford and colleagues (2020) recommended that visual support planning be based on developmental stages rather than on chronological age, and Park and Zuniga (2016) promoted the practice of using developmentally appropriate language for client educational materials. Using a developmentally based reading comprehension measure rather than basing ability on the number of years one has attended school, meets clients at an individual level, which can improve confidence and promote self-representation.

Applying UDL and Text Analysis to a Community Participation Program

The Planning for Autism in Communities and Schools program (Fletcher et al., 2021) is a sustainable education and sensory audit-based approach to promoting participation for people impacted by ASD in community settings and schools. To accomplish this, we created a curriculum to support students with ASD as they navigate these locations, helping them develop a greater self-awareness of the sensory, communication, and social and behavioral factors that impact their participation. Our curriculum relies heavily on UDL and text-analysis measurements to help students master their learning objectives.

One activity we implement involves students’ responses to simulated community outings. We follow procedures that integrate UDL and text levels with goals of promoting exposure, processing, and problem solving. First, we walk through the community setting (e.g., a restaurant), videotaping the parking lot, entryway, restrooms, drinking fountains, and other related elements. The video emphasizes signage, seating, exits, and degrees of crowding. The video is then broken down topically into 60- to 180-second segments, which are embedded in a facilitator-driven PowerPoint presentation used for analysis and interactive discussion with the students who participated in the outing. Photographs, visual images and icons, or other graphics are used to query students about how to optimally participate in the community experience. Students then respond to questions about the sensory, communication, and social factors of the community setting using differentiated text or graphic prompts.

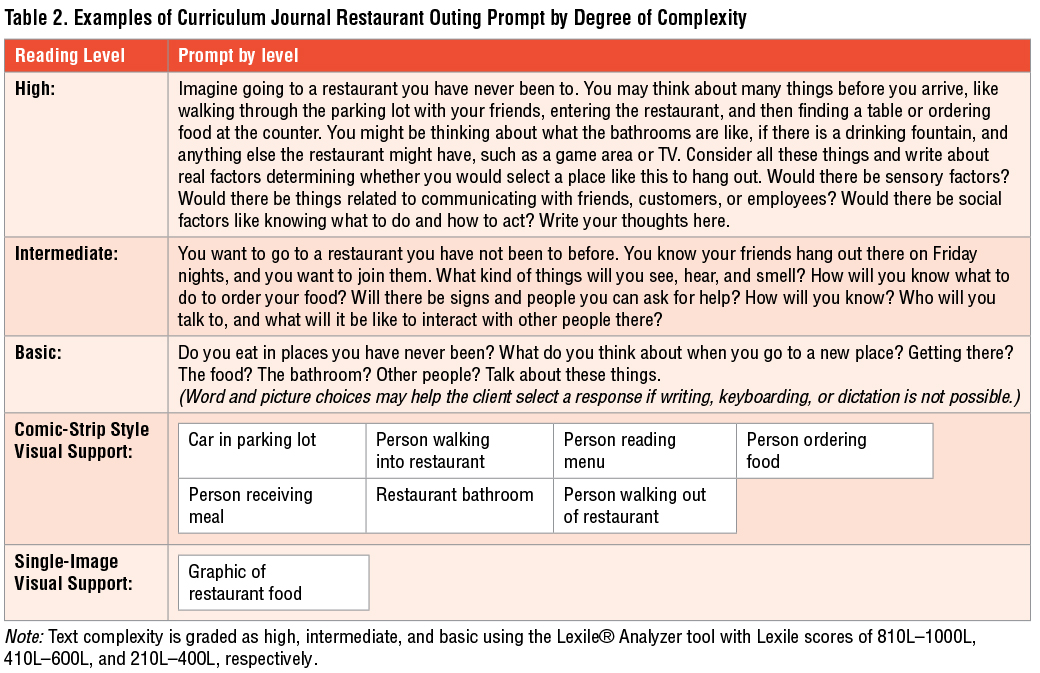

By using this variety of methods and modalities, students participating in the program have benefitted from the UDL principles of multiple paths to engagement, representation, and action and expression. In our experience, students in their UDL plus text- and graphics-enriched classroom are actively participating in their learning and knowledge construction, which encourages engagement. In fact, one of the greatest challenges in our program is students loitering around the classroom entrance wanting more. Table 2 shows examples of curriculum journal prompts using text analysis and graphics to achieve program goals.

Conclusion

By embracing the concepts of UDL and text analysis to plan sessions and client education materials, OTPs can have a reliable and replicable recipe for success to ensure that client curriculum promotes occupation, advances inclusion, and provides opportunities for participation in the community.

References

Baxter, J., Rutherford, M., & Holmes, S. (2015). The visual support project (VSP): An authority-wide training, accreditation and practical resource for education settings supporting inclusive practice. Communication Matters, 29(2), 9–13. https://www.communicationmatters.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/cmj_vol_29_no_2_3fx.pdf

CAST, Inc. (2021). The UDL guidelines. https://udlguidelines.cast.org/?utm_source=castsite&lutm_medium=web&utm_campaign=none&utm_content=aboutudl

Fletcher, T., Garcia, N., & Marlin, A. (2021, April 13–14). Promoting community inclusion and participation for people with autism [Poster presentation]. Texas Woman's University 24th Annual Student Creative Arts and Research Symposium, Denton, TX, United States. https://hdl.handle.net/11274/12836

Hayes, G., Hirano, S., Marcu, G., Monibi, M., Nguyen, D. H., & Yeganyan, M. (2010). Interactive visual supports for children with autism. Personal and Ubiquitous Computing, 14, 663–680. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00779-010-0294-8

Higher Education Opportunity Act, 20 U.S.C. § 1001 et seq. (2008). https://www2.ed.gov/policy/highered/leg/hea08/index.html

McMahon, D., & Walker, Z. (2019). Leveraging emerging technology to design an inclusive future with universal design for learning. Career Development and Transition for Exceptional Individuals, 42(2), 99–110. https://doi.org/10.26529/cepsj.639

MetaMetrics, Inc. (2020). Lexile® and Quantile Tools. The Lexile® framework for reading. https://hub.lexile.com/find-a-book/search

Park, J., & Zuniga, J. (2016). Effectiveness of using picture-based health education for people with low health literacy: An integrative review. https://doi.org/10.1080/2331205X.2016.1264679

Rutherford, M., Baxter, J., Grayson, Z., Johnston, L., & O’Hare, A. (2020). Visual supports at home and in the community for individuals with autism spectrum disorders: A scoping review. Autism, 24(2), 447–469. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1362361319871756

Saunders, P. (2018). Neurodivergent rhetorics examining competing discourses of autism advocacy in the public sphere. Journal of Literary & Cultural Disability Studies, 12(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.3828/jlcds.2018.1

Angela L. Marlin, OTR, MOT, is a clinical therapist at the Warren Center, a non-profit pediatrics clinic in Richardson, TX. Angela also works as a PRN therapist at an adult inpatient rehabilitation hospital in the Dallas-Fort Worth area.

Tina S. Fletcher, EdD, MFA, OTR, is a professor in the School of Occupational Therapy at Texas Woman’s University, Dallas Center. She is a certified school therapy specialist, and her areas of focus and research interests include creative arts interventions and access programming.

Natalie M. Garcia, OTR, MOT, is an acute care therapist with Baylor Scott & White Health in Dallas, TX.

This study was funded by the Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board, award number #22973, as part of an Innovative ASD Treatment Models grant.