Post Intensive Care Syndrome (PICS): OT's role in ADL and IADL assessment

Meet Jimmy

Jimmy, a 38-year-old male, was admitted to the intensive care unit at a large academic institution in November 2021 with SARS-CoV-2 infection, complicated by respiratory failure, COVID pneumonia, and sepsis. Jimmy was a self-employed contractor, and prior to his illness he enjoyed riding his motorcycle on weekends. He lived with his significant other, and together they independently managed all IADLs. During his intensive care stay, Jimmy was intubated for 6 days before being extubated and transferred to a medical floor. He spent 12 days there and received occupational therapy and physical therapy services. At discharge, the medical team was pleased with his physical progress, but the occupational therapy practitioner did note several safety, problem solving, and memory concerns.

Within days of discharge, it became apparent that Jimmy’s daily life did not return to his prior level of function. He was struggling to afford the hospital bills, as he was unable to return to work (or manage his company bookkeeping). He was also having trouble keeping up with housework, medical appointments, and new medication regimens. Additionally, Jimmy had difficulty falling asleep and was awakening frequently with frightening dreams. When Jimmy attended his initial evaluation at the outpatient critical illness recovery follow-up clinic 3 weeks post-discharge, he was frustrated and disheartened.

Post Intensive Care Syndrome

Jimmy’s story is emblematic of many critical illness survivors (Needham et al., 2012). Post Intensive Care Syndrome (PICS) has drawn considerable attention in recent years. Patients discharged from the hospital after critical illness often have residual physical, cognitive, and mental health deficits that go unaddressed by health care professionals (Needham et al, 2012). Most problematic are impairments such as fatigue, post-traumatic stress, anxiety, poor executive functioning, and poor memory, which are common and are frequently underrecognized. As with Jimmy, many patients can independently ambulate and complete basic ADLs, but these more subtle, underlying deficits impact higher level activities and community participation. Deficits can last months—or even years—after the initial illness, and significantly impact engagement in meaningful occupations in the home and community. The deficits from PICS are similar to the condition that has been referred to as “long COVID” by scientists and health care professionals. PICS, though, is specific to all critical illness survivors, whereas long COVID may impact any individual after a COVID-19 infection (Chippa et al., 2022).

The Role of the Occupational Therapist in Identifying PICS

Recognition of these lasting impacts has led to the development of specialty critical illness follow-up clinics—particularly in areas with large trauma centers—to screen for PICS, and to refer patients for services to reduce potential long-term deficits and to combat PICS (Modrykamien, 2012; Sevin et al., 2018). These multi-disciplinary clinics employ a variety of health care professionals, including physicians, nurse practitioners, dieticians, pharmacists, occupational therapy practitioners, physical therapists, and speech-language pathologists to address the multi-faceted needs of critical illness survivors. The unique role of the occupational therapy practitioner in the clinic is to screen for ADL, IADL, and functional cognition deficits to determine if the individual requires additional support services in their current living situation. Here, we detail specific practices that the occupational therapist can use to support these critical activities.

ADLs and IADLs Assessment in Critical Illness Survivors

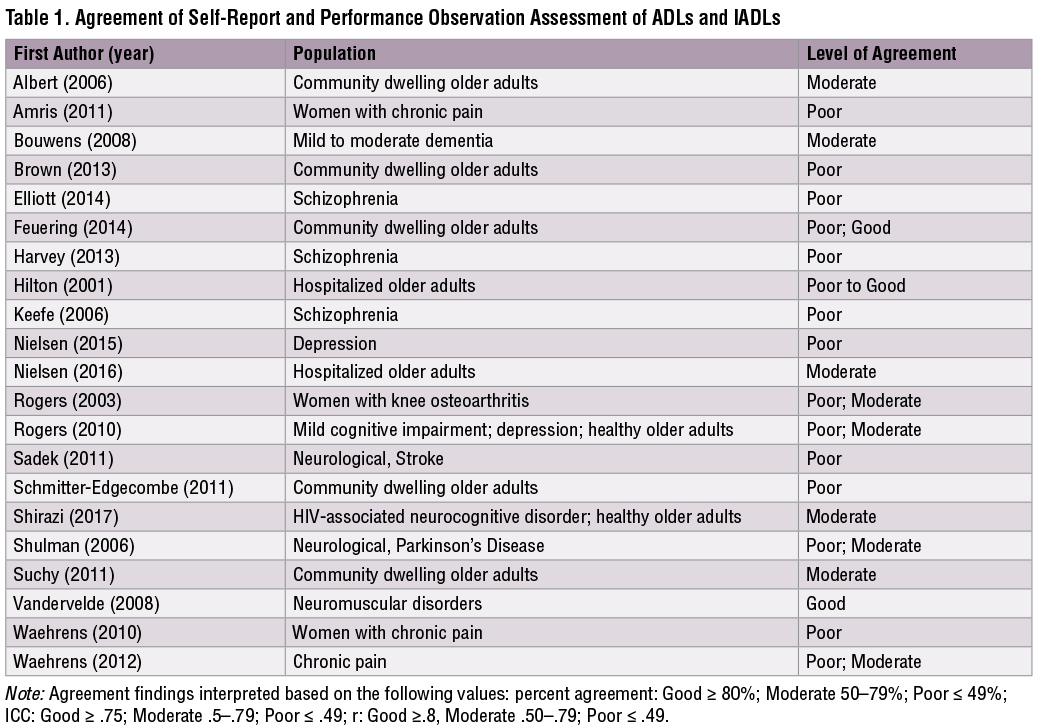

As in other settings, occupational therapy practitioners in critical illness follow-up clinics often administer self-report measures to assess mobility, cognition, and ADL and IADL independence. Self-report measures are easy to access, quick to administer, and low in cost to the provider and patient. However, historically, many practitioners have questioned the accuracy of self-report measures to reflect actual performance of ADLs and IADLs (Bravell et al., 2011; Depp et al., 2009; Mitchell & Miller, 2008; Thames et al., 2011). Some practitioners argue that performance observation assessment—where skilled raters observe patients performing ADLs and rate them using standardized tasks and rating scales—should be used to obtain this essential information (Moore et al., 2007). In fact, a scoping review examining studies published between January 2000 and April 2020 identifies numerous examples of moderate or poor concordance between self-report and performance observation assessments of ADLs and IADLs in studies of adults with various chronic conditions (see Table 1). Given the similarities between these conditions and PICS, it is likely that these findings may also apply to PICS populations.

Self-Report and Performance Observation in Critical Illness Survivors

In a sample of patients at a critical illness follow-up clinic (N=6), we examined the concordance between two self-report assessments typically administered at the critical illness recovery centers: Katz ADL (Katz et al., 1963) and Lawton IADL (Lawton et al., 1969), and nine items from a performance observation assessment of ADL and IADL, the Performance Assessment of Self-Care Skills (Rogers & Holm, 1994). We found moderate to low levels of agreement between critical illness survivors’ reports and their performance of ADLs and IADLs (range 0%–60%), with a trend toward reporting lower performance than what was observed. These findings suggest that self-report and performance observation assessments of ADLs and IADLs yield different information and cannot be assumed to be interchangeable after critical illness. Thus, occupational therapy practitioners should use a battery of assessment types to screen for residual deficits after critical illness.

Jimmy’s PICS Clinic Evaluation

At Jimmy’s PICS clinic evaluation, 3 weeks post-hospital discharge, the clinic staff administered brief self-report measures of ADLs and IADLs. From these they determined that Jimmy was independent with ADLs and required assistance with several IADLs. Jimmy’s occupational therapy practitioner then administered a performance observation assessment of cognitive and physical IADLs including shopping, paying bills, writing checks, mailing bills, managing medication, using the phone, and sweeping. Jimmy’s scores indicated that he was able to independently complete all the tasks with minimal verbal and visual cues. Jimmy reported higher functional ability than what was observed during completion of the cognitive IADL tasks and lower functional ability than what was observed in the completion of physical IADL tasks. The two types of assessments provided the occupational therapy practitioner with different information, which helped guide treatment.

Implications for Practice

When practitioners administer a self-report assessment in patients presenting with PICS, they may not be capturing the full picture of disability. As occupational therapy practitioners working with critical illness survivors, it is imperative for us to ensure that we are acquiring enough information to determine if our clients have residual deficits in ADLs, IADLs, and functional cognition so we can ensure that they receive proper follow-up care. The ramifications of inaccurate assessment include patients not receiving appropriate care, residual deficits going unnoticed, or inefficient use of health care resources.

Although self-report measures are quick and easy to administer, the information gathered may not be fully capturing the patient’s ability or independence level. Patients may report levels that are higher or lower than what is directly observed during performance assessment. Higher reports may indicate an overestimation of abilities, while lower reports may indicate a degree of learned helplessness. Occupational therapy practitioners working with this population should use caution when interpreting self-report assessments of ADLs and IADLs to ensure they are capturing accurate levels of independence and providing the most effective interventions.

Conclusion

A common perception is that performance observation assessments take longer than others to administer, are not easily accessible, and require additional training that is difficult to maintain in practice. Although this is true for some performance observation assessments, others, such as those used in Jimmy’s case, can be completed in 5 to 10 minutes and are freely available. Practitioners can utilize these tools to increase accuracy with ADL and IADL assessment among critical illness survivors to guarantee they receive appropriate follow-up services to return to their maximal level of independence. As with Jimmy, we can accurately assess independence to develop a plan of care that ensures our clients have every opportunity for recovery.

References

Albert, S. M., Bear-Lehman, J., Burkhardt, A., Merete-Roa, B., Noboa-Lemonier, R., & Teresi, J. (2006). Variation in sources of clinician-rated and self-rated instrumental activities of daily living disability. Journals of Gerontology: Series A, 61(8), 826–831. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/61.8.826

Amris, K., Waehrens, E. E., Jespersen, A., Bliddal, H., & Danneskiold-Samsøe, B. (2011). Observation-based assessment of functional ability in patients with chronic widespread pain: A cross-sectional study. Pain, 152, 2470–2476. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2011.05.027

Bouwens, S. F., Van Heugten, C. M., Aalten, P., Wolfs, C. A., Baarends, E. M., Van Menxel, D. A., & Verhey, F. R. (2008). Relationship between measures of dementia severity and observation of daily life functioning as measured with the Assessment of Motor and Process Skills (AMPS). Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders, 25(1), 81–87. https://doi.org/10.1159/000111694

Bravell, M. E., Zarit, S. H., & Johannsson, B. (2011). Self-reported activities of daily living and performance-based functional ability: A study of congruence among the oldest old. European Journal of Ageing, 8(3), 199–209. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10433-011-0192-6

Brown, C. L., & Finlayson, M. L. (2013). Performance measures rather than self-report measures of functional status predict home care use in community-dwelling older adults. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 80(5), 284–294. https://doi.org/10.1177/0008417413501467

Chippa, V., Aleem, A., & Anjum, F. (2022). Post acute coronavirus (COVID-19) syndrome. StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK570608/

Depp, C. A., Mausbach, B. T., Eyler, L. T., Palmer, B. W., Cain, A. E., Lebowitz, B. D., … Jeste, D. V. (2009). Performance-based and subjective measures of functioning in middle-aged and older adults with bipolar disorder. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 197(7), 471–475. https://doi.org/10.1097/NMD.0b013e3181ab5c9b

Elliott, C. S., & Fiszdon, J. M. (2014). Comparison of self-report and performance-based measures of everyday functioning in individuals with schizophrenia: Implications for measure selection. Cognitive Neuropsychiatry, 19(6), 485–494. https://doi.org/10.1080/13546805.2014.922062

Feuering, R., Vered, E., Kushnir, T., Jette, A. M., & Melzer, I. (2014). Differences between self-reported and observed physical functioning in independent older adults. Disability and Rehabilitation, 36(17), 1395–1401. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638288.2013.828786

Harvey, P. D., Stone, L., Lowenstein, D., Czaja, S. J., Heaton, R. K., Twamley, E. W., & Patterson, T. L. (2013). The convergence between self-reports and observer ratings of financial skills and direct assessment of financial capabilities in patients with schizophrenia: More detail is not always better. Schizophrenia Research, 147(1), 86–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2013.02.018

Hilton, K., Fricke, J., & Unsworth, C. (2001). A comparison of self-report versus observation of performance using the Assessment of Living Skills and Resources (ALSAR) with an older population. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 64(3), 135–143. https://doi.org/10.1177/030802260106400305

Katz, S., Ford, A. B., Moskowitz, R. W., Jackson, B. A., & Jaffe, M. W. (1963). Studies of illness in the aged. The index of ADL: A standardized measure of biological and psychosocial function. JAMA, 185, 914–919. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.1963.03060120024016

Keefe, R. S., Poe, M., Walker, T. M., Kang, J. W., & Harvey, P. D. (2006). The Schizophrenia Cognition Rating Scale: An interview-based assessment and its relationship to cognition, real-world functioning, and functional capacity. American Journal of Psychiatry, 163, 426–432. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.163.3.426

Lawton, M. P., & Brody, E. M. (1969). Assessment of older people: Self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist, 9(3), 179–186. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/9.3_Part_1.179

Mitchell, M., & Miller, L. S. (2008). Executive functioning and observed versus self-reported measures of functional ability. Clinical Neuropsychologist, 22, 471–479. https://doi.org/10.1080/13854040701336436

Modrykamien, A. M. (2012). The ICU follow-up clinic: A new paradigm for intensivists. Respiratory Care, 57(5), 764–772. https://doi.org/10.4187/respcare.01461

Moore, D. J., Palmer, B. W., Patterson, T. L., & Jeste, D. V. (2007). A review of performance-based measures of functional living skills. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 41(1–2), 97–118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2005.10.008

Needham, D. M., Davidson, J., Cohen, H., Hopkins, R. O., Weinert, C., Wunsch, H., … Harvey, M. A. (2012). Improving long-term outcomes after discharge from intensive care unit: Report from a stakeholders' conference. Critical Care Medicine, 40(2), 502–509. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0b013e318232da75

Nielsen, K. T., & Waehrens, E. E. (2015). Occupational therapy evaluation: Use of self-report and/or observation? Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 22(1), 13–23. https://doi.org/10.3109/11038128.2014.961547

Nielsen, L. M., Kirkegaard, H., Østergaard, L. G., Bovbjerg, K., Breinholt, K., & Maribo, T. (2016). Comparison of self-reported and performance-based measures of functional ability in elderly patients in an emergency department: Implications for selection of clinical outcome measures. BMC Geriatrics, 16(1), 199. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-016-0376-1

Rogers, J. C., & Holm, M. B. (1994). Performance Assessment of Self-Care Skills (PASS - Home) Version 3.1 [Unpublished assessment tool]. University of Pittsburgh.

Rogers, J. C., Holm, M. B., Beach, S., Schulz, R., Cipriani, J., Fox, A., & Starz, T. W. (2003). Concordance of four methods of disability assessment using performance in the home as the criterion method. Arthritis Care & Research, 49, 640–647. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.11379

Rogers, J. C., Holm, M. B., Raina, K. D., Dew, M. A., Shih, M. M., Begley, A., … Reynolds III, C. F. (2010). Disability in late-life major depression: Patterns of self-reported task abilities, task habits, and observed task performance. Psychiatry Research, 178, 475–479. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2009.11.002

Sadek, J. R., Stricker, N., Adair, J. C., & Haaland, K. Y. (2011). Performance-based everyday functioning after stroke: Relationship with IADL questionnaire and neurocognitive performance. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society, 17(5), 832–840. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1355617711000841

Schmitter-Edgecombe, M., Parsey, C., & Cook, D. J. (2011). Cognitive correlates of functional performance in older adults: Comparison of self-report, direct observation, and performance-based measures. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society, 17(5), 853–864. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1355617711000865

Sevin, C. M., Bloom, S. L., Jackson, J. C., Wang, L., Ely, E. W., & Stollings, J. L. (2018). Comprehensive care of ICU survivors: Development and implementation of an ICU recovery center. Journal of Critical Care, 46, 141–148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrc.2018.02.011

Shirazi, T. N., Summers, A. C., Smith, B. R., Steinbach, S. R., Kapetanovic, S., Nath, A., & Snow, J. (2017). Concordance between self-report and performance-based measures of everyday functioning in HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders. AIDS and Behavior, 21, 2124–2134. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-017-1689-6

Shulman, L. M., Pretzer‐Aboff, I., Anderson, K. E., Stevenson, R., Vaughan, C. G., Gruber‐Baldini, A. L., … Weiner, W. J. (2006). Subjective report versus objective measurement of activities of daily living in Parkinson's disease. Movement Disorders, 21, 794–799. https://doi.org/10.1002/mds.20803

Suchy, Y., Kraybill, M. L., & Franchow, E. (2011). Instrumental activities of daily living among community-dwelling older adults: Discrepancies between self-report and performance are mediated by cognitive reserve. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology, 33(1), 92–100. https://doi.org/10.1080/13803395.2010.493148

Thames, A. D., Becker, B. W., Marcotte, T. D., Hines, L. J., Foley, J. M., Ramezani, A., … Hinkin, C. H. (2011). Depression, cognition, and self-appraisal of functional abilities in HIV: An examination of subjective appraisal versus objective performance. Clinical Neuropsychologist, 25(2), 224–243. https://doi.org/10.1080/13854046.2010.539577

Vandervelde, L., Dispa, D., Van den Bergh, P. Y., & Thonnard, J. L. (2008). A comparison between self-reported and observed activity limitations in adults with neuromuscular disorders. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 89, 1720–1723. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2008.01.024

Waehrens, E. E., Amris, K., & Fisher, A. G. (2010). Performance-based assessment of activities of daily living (ADL) ability among women with chronic widespread pain. Pain, 150, 535–541. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2010.06.008

Waehrens, E. E., Bliddal, H., Danneskiold-Samsøe, B., Lund, H., & Fisher, A. G. (2012). Differences between questionnaire- and interview-based measures of activities of daily living (ADL) ability and their association with observed ADL ability in women with rheumatoid arthritis, knee osteoarthritis, and fibromyalgia. Scandinavian Journal of Rheumatology, 41(2), 95–102. https://doi.org/10.3109/03009742.2011.632380

Avital S. Isenberg, CScD, MS, OTR/L, is an Instructor at the University of Pittsburgh and a staff occupational therapist at an acute care hospital in Pittsburgh, PA.

Jennifer S. White, CScD, MOT, OTR/L, is an Assistant Professor with the Department of Occupational Therapy at the University of Pittsburgh.

Leslie P. Scheunemann, MD, MPH, is an Assistant Professor of Geriatrics and Pulmonary, Allergy, and Critical Care Medicine at the School of Medicine at the University of Pittsburgh.

Maria Shoemaker, OTR/L, is an Occupational Therapist at the Critical Illness Recovery Center at UPMC Mercy in Pittsburgh, PA.

Juleen Rodakowski, OTD, MS, OTR/L, is an Associate Professor in the Department of Occupational Therapy at the University of Pittsburgh.

Elizabeth R. Skidmore, PhD, OTR/L, is Professor and Chair in the Department of Occupational Therapy and Associate Dean for Research in the School of Health and Rehabilitation Sciences at the University of Pittsburgh.